Why Higher Inflation Might Mean You Shouldn’t Pay Off Your Low-Interest Debt Early

Listen, let’s just address one thing upfront: I am not someone who believes all debt is bad.

I know this is a very popular debate (and it’s become increasingly fashionable to rank your own stance on debt in relation to Dave Ramsey’s), but my opinion is (mostly) informed by the data available to me. And also, I don’t like Dave.

I don’t say that to make myself sound smart (as I’ve said more times than I can count, I’m a dumbass with a PR degree). I say it because I think there are two approaches to debt:

The emotional approach, and the rational one.

In fact, I have this conspiracy theory that this notion that all debt is bad is actually a lie that the ultra wealthy sell to middle class America because leveraging debt strategically is how the rich get richer.

It’s literally called “leverage.”

It’s how rental property investing and buying stocks on margin works. You use other people’s money (or borrow against your own money) to make more money.

Rich people take out debt to create more wealth all the time, so this myopic, black-and-white approach to debt that it’s all terrible and — regardless of the interest rate — you need to pay it off as fast as possible is simply too much of a “blunt force trauma” attitude for me.

What does debt have to do with inflation?

Unless you’re living under a pile of weighted blankets watching Kardashians re-runs all day (guilty), you’ve probably seen headlines about inflation. For the first time since 1990, inflation is hovering around 5%.

While inflation is a big, hairy economic topic, all you need to know for the purposes of this post in a practical sense is that it means the dollar that you have in your pocket right now can buy more today than it’ll buy tomorrow (assuming the inflationary trends continue).

The value of a single dollar is going down.

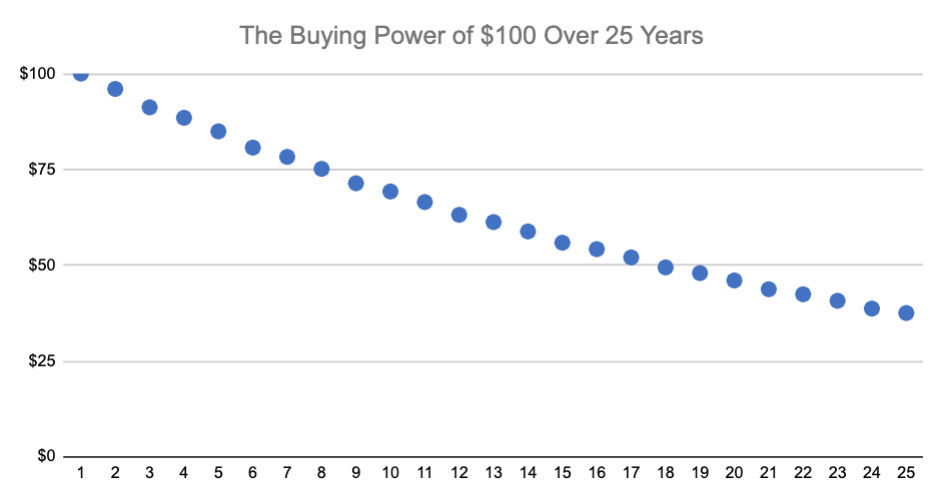

When I say the “value,” I mean the purchasing power in today’s dollars – so in year 1, spending $100 is like… well, spending $100.

But what about after 25 years?

Even if inflation hovers between 3-5% (alternating 3%, 4%, and 5% each year, then cycling back to 3%), $100 in 25 years from now will have the equivalent buying power of $37.51 today.

This looks like this:

So what does this have to do with debt?

Imagine you take out a loan that lasts 25 years, and every month, you owe $100.

Your debt repayment doesn’t adjust with inflation – it’s a flat $100 for the duration of the loan

Since your debt doesn’t adjust for inflation, your debt literally becomes cheaper over time.

The overall payment is worth less to you as the value of your dollar buys less over time.

When you first look at that graph, it can look like the opposite is true: That your $100 is worth less over time, so you need more money to pay the debt. But the amount that you owe stays consistent, and everything else (theoretically) goes up with inflation, like the cost of other goods and your income.

This is conceptually similar to why people are horny for mortgages – because the cost of your housing in 30 years from now stays consistent with the cost today, unlike rents, which theoretically rise over time.

Use an example from your grandma

You know how your grandparents lament about how a cheeseburger used to cost a dime and their annual salaries were $15,000 per year?

It’s like that.

Today, you can get a chicken sandwich from Chick-Fil-A for about $5.

That means $100 in 2021 = 20 Chick-Fil-A sandwiches. Bless.

As the value of your dollar goes down over time because of increased money supply (inflation), a chicken sandwich goes up in price. It might look like this, assuming the same rotating 3-5% inflation:

After 25 years, the same chicken sandwich costs $12.81.

That means the $100 that used to be able to buy 20 chicken sandwiches can now (after 25 years) only buy 7.8 sandwiches (we’ll round up and say we threw in waffle fries).

Using this ridiculous example, why would you hand over an extra $100 now (when your money is worth 20 sandwiches!) than delaying that $100 payment into the future when it’s still $100, but only has 8-sandwiches-worth of purchasing power?

Obviously, you need to make minimum payments on your debt – and high interest debt is a different story – but for low-interest debt, the power of inflation is melting away the value of your money as the amount that you owe each month stays the same.

When you consider the fact that you can invest extra payments to grow faster than inflation and couple it with the fact that inflation is rising and making your money worth less faster, it makes it feel silly to pay down low-interest debt early.

Put ridiculously, why would you pay off your debt with 20 chicken sandwiches now when you can pay 8 chicken sandwiches later, just to be “done” faster?

How income is impacted by inflation

Most workplaces worth their weight in Microsoft Outlook will increase your salary every year by 2-3% by default to account for inflation (whether or not this is a tenable long-term economic strategy is questionable, but the point stands).

That means your income goes up with inflation – because next year, you have to make more than $100 to be able to buy what $100 buys today.

Using the exact same inflationary trend and applying it to income that keeps up with inflation, you get this:

Over the lifetime of this hypothetical 25-year loan, you can see that your debt repayment remains the same while the equivalent of $100 that you’re paid goes up.

It doesn’t matter to the lender that in year 10 you’re getting $150 to be able to purchase the equivalent of what $100 buys today. You still owe them $100.

Thanks to the sponsor of this post, Fundrise.

I invested $5,000 into Fundrise, which provides the average retail investor access to institutional quality private real estate deals that were formerly unavailable to the public.

Less volatile than public REITs, Fundrise has been a neat way for me to get some skin in the real estate game without bearing the burden of being tied to one home (and its maintenance, taxes, insurance, and interest).

The minimum investment is $10, but it’s rather illiquid – you can’t get your money out before year 5, as the money is actually used to purchase properties (much like, well, buying an actual house).

You can learn more about investing with Fundrise here.