Why You Should Consider Investing in Index Funds & ETFs in 2025

May 5, 2021

The Wealth Planner

The only personal finance tool on the market that’s designed to transform your plan into a path to financial independence.

Get The Planner

Subscribe Now

Biggest Finance Newsletter for Women

More than 10 million downloads and new episodes every Wednesday.

The Money with Katie Show

Recommended Posts

A far more robust version of this blog post lives in Chapter 3 of Rich Girl Nation, “Knowledge is Power.” Grab your copy now!

One of the most interesting things about blogging about personal finance (and, by extension, creating an Instagram presence that just screams, “Send me your deepest, darkest fears about investing!”) is that the way questions are phrased reveals a lot about the deep misunderstanding most of us have about how investing actually works.

For example, a question I receive more than I’d like to: “Should I invest in my 401(k) or index funds?”

There’s absolutely no shame in not understanding—after all, when would you have learned this stuff unless you took an active interest?

But 401(k)s and index funds are not an either/or. That’s like asking, “Should I eat fruit or strawberries?”

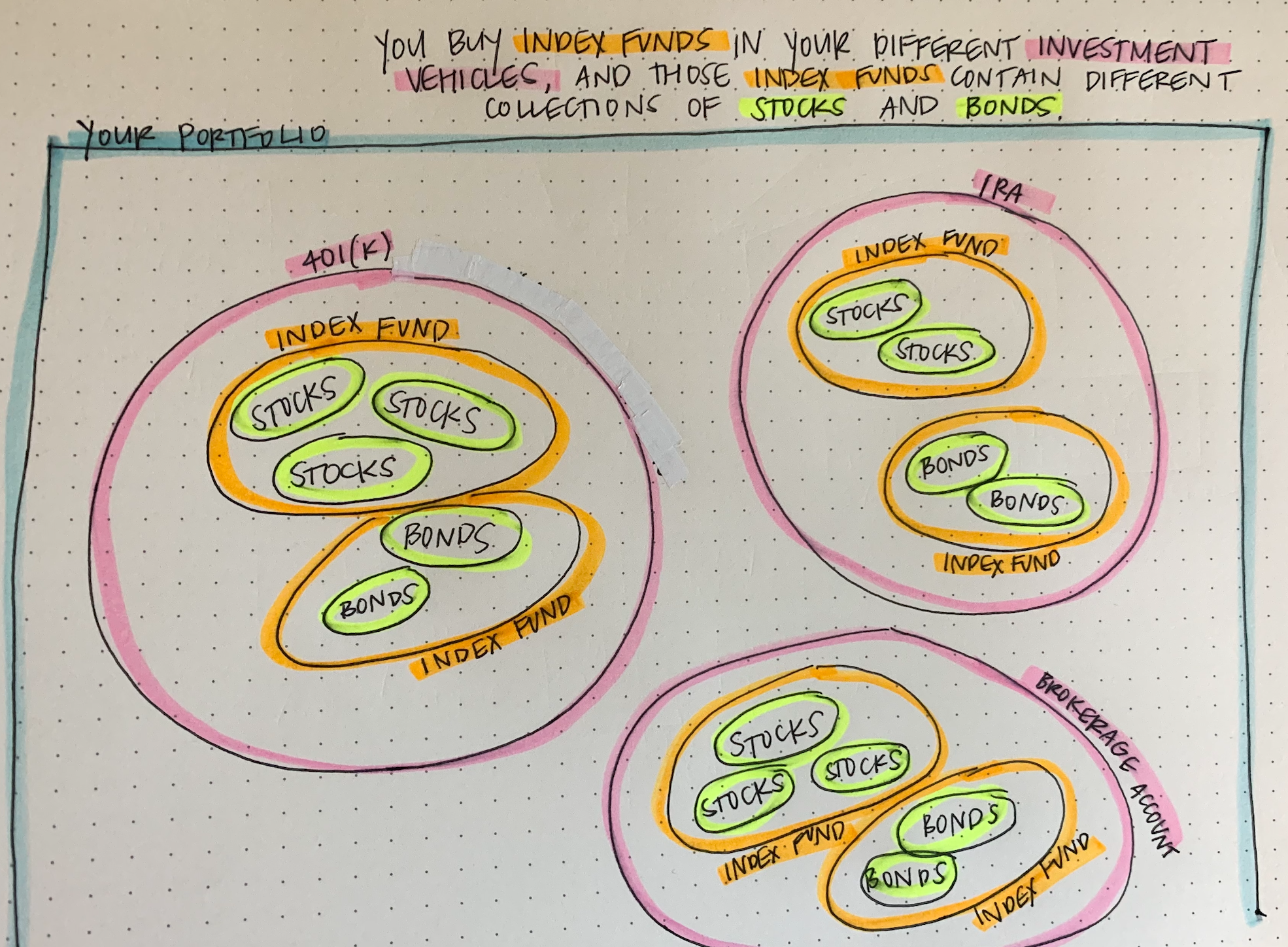

The strawberries are INSIDE the “fruit” category. I recently posted a picture that explains how all these terms are related:

Graphic design is my passion.

The good news is that people are asking about index funds, which are, in my opinion, one of the absolute best ways for any individual investor to do really well in the stock market.

Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, invented the index fund in 1975 and pretty much immediately pissed off and amused every big wig on Wall Street.

The premise of an index fund—that you aren’t trying to purchase individual stocks, but instead buying a fund that tracks an index—was a wild idea at the time. At first, people ridiculed Jack for suggesting investors should stop looking for the needle in the haystack and instead buy the entire haystack. How could that possibly compete against making educated guesses at which stocks would perform best? As you can probably guess, his critics promptly shut the hell up after a few years of his index funds crushing.

Why is it so hard to pick individual stocks? It has a lot to do with the fact that our perception of successful companies is very relative and skewed to our own present-day experience and biases.

Only one of the original 30 companies listed on the Dow Jones Industrial Average is still around, General Electric. Companies, industries, and the world around them changes—and usually, those changes are gradual, complex, and not obviously correlated to one another.

Once a company becomes an obvious “winner” as defined by its stature in the market, most of its explosive growth has already happened: Someone who purchased $1,000 worth of Apple stock in the 1990s when all the pundits were claiming it was a loser that would never get asked to prom saw some serious returns.

But someone who buys Apple today? Apple already popped off. The ugly duckling already had its glow-up. Nobody’s laughing at you if you buy Apple now. Sure, you’ll see growth, but will it compare to the get-rich-quick windfall that nerds in the 90s predicted when Wall Street was scoffing? Unlikely. Apple was a shooting star.

…and basing your investment strategy on your ability to seek out shooting stars is probably going to net you majority losses. Things change.

“Consider that in the 1960s the U.S. government was seriously considering (it never happened) the forced breakup of General Motors. GM was deemed so dominant and powerful that no other car company could compete. This is the same GM that survives today only by the grace of a huge bailout by that same government. On the other hand, back in the 1990s the smart money was betting Apple might not survive. As of this writing, it is the single largest U.S. company as measured by market capitalization. Today’s stars are tomorrow’s wrecks. Today’s fallen are tomorrow’s exciting turnarounds,” writes J.L. Collins in his 2016 book, The Simple Path to Wealth.

Why is it so hard for some of us to accept that picking individual stocks can ultimately net losses over time, or underperform index investing as a whole? Because we’re prideful and stupid. Just kidding (about the second part). The people I see struggle with this the most are the really smart ones: It’s hard to wrap your big brain around the fact that you’ll do better by doing nothing. It flies in the face of the way we’re taught to approach every other aspect of our lives – but investing isn’t like the other aspects of your life.

Being a successful investor comes down to a few counterintuitive principles: Being okay with boredom 90% of the time (slow growth over time) and terror 10% of the time (March 2020 COVID plummet), coupled with extreme patience.

Index investing isn’t exciting—it’s generally stable.

So what’s investing anyway?

In its simplest form, investing means you’re buying a little piece of a company. You’re not just buying a piece of paper or a number on a screen; you’re not dumping your money into an account where you’ll earn a guaranteed interest rate (another weirdly common misconception). When you invest, you’re becoming a part owner of a company—or hundreds, or thousands of them, depending on what you buy—and as that company makes money, so do you. That’s really all there is to it.

If that company loses money, so do you. This is the nauseating downside to the Apple narrative: It’s the reason individual stock investing is a double-edged sword. There are other companies that have gone from market darling to out of business just as quickly, turning whatever amount you invested into a gut-wrenching $0.

That’s why index funds like those that track the S&P 500 can be so great: Because you own pieces across the largest 500 companies in the United States, you own an index that automatically filters out certain companies, without you doing a damn thing.

Say you own an S&P 500 index fund (like VFINX, the Vanguard S&P 500 index fund, or the ETF version, VOO), you can own pieces of:

-

Apple Inc. (AAPL)

-

Microsoft Corp. (MSFT)

-

Amazon.com Inc. ( AMZN)

-

Facebook Inc. (FB)

-

Tesla Inc. (TSLA)

-

Alphabet Inc. Class A Shares (GOOGL)

-

Alphabet Inc. Class C Shares (GOOG)

-

Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (BRK.B)

And about 490 more. As companies grow and become successful, they can automatically get added to that index. As they start to shit the bed and shrink, they can be dropped— automatically.

Some financial gurus, like Paul Merriman, take the opposite approach and promote small-cap value index funds (in other words, suggest owning index funds that comprise hundreds of the smallest companies), the logic being that every Apple, Tesla, and Microsoft once started out as a fledgling baby before they became breakout stars.

If you wait until they crack the top 500, it’s likely that a lot of the explosive growth has already happened—thus the argument for owning the #SmallBoiz too, knowing the risk that most of them will fizzle and die—but if you own one or two future shooting stars, it could create a lot of growth.

Other approaches

Of course, another approach is buying the entire market in a fund like VTSAX (ETF: VTI), the Vanguard Total Stock Market fund. When you own the entire market, you’re buying the entire haystack—not just a subset of it. The tricky thing is that big companies are given preference in index funds, by nature of the fact that they’re bigger.

And while we won’t get into a deep dive today on an optimal way to structure your portfolio (hint: this is hotly contested and there are many competing schools of thought, as you may be able to tell already), it’s important to know that index funds require you to abandon your get-rich-quick fantasies and gambling tendencies and instead subscribe to the get-rich-slowly-and-steady plan.

“Great, I’m in. But what’s the difference between an index fund and an ETF?”

Ah, yes, the other great confusing topic with no great answer.

Investing is always evolving. Remember how the index fund was invented in the 70s? The ETF was invented in the 90s, and it stands for “exchange-traded fund.”

It basically just means it’s an index fund that, instead of trading once per day, can trade throughout the day as if it were an individual stock. You can get index funds (or ETFs) that track all sorts of indices: the tech sector, small companies, bonds, etc.

What does that mean for us? Nothing, really, except for the fact that they usually have slightly lower expense ratios (read: costs) and lower barriers to entry.

Where to buy index funds and ETFs

You can buy ETFs in any investment account, and it’s really easy to open one. Your 401(k). Your Roth IRA. Your taxable investing account. Your boyfriend’s sister’s 401(k)! These puppies are everywhere, and you’d probably benefit from an audit of what you’re invested in in these various accounts. Happy index investing!

Looking for something?

Search all how-to, essays, and podcast episodes.

Explore

While I love diving into investing- and tax law-related data, I am not a financial professional. This is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational and recreational purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, index funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. Do your own due diligence. Past performance does not guarantee future returns.

Money with Katie, LLC.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

This Site Was Built by Brand Good Time